Martin Whitman founded Third Avenue Value Fund some twenty years ago. Over that time period, the fund has beaten the returns of the S&P 500 by several points annually. In The Aggressive Conservative Investor, Whitman collaborates with Martin Shubik to discuss a concept that they call "safe and cheap" investing.

This chapter is about the various forms of accounting and their uses. The authors argue that accounting is the single most important tool in making sense of a business. It is the language of business, and investors who seek to understand companies must become fluent in it.

The distinctions between the following forms of accounting are discussed: cost accounting, tax accounting, and financial accounting. The authors argue that they each have their purpose, and noting the distinctions between them will help investors understand the limitations of financial accounting, which is the form of accounting used by investors.

For example, the authors argue that it is a misconception that the relative efficiencies of competing companies can be determined using financial accounting. There are too many assumptions that managements are free to make in financial accounting to allow for such direct comparison. To truly compare efficiencies between companies, one would have to have access to numerous internal (i.e. non-public) documents.

The authors also distinguish between financial accounting as used for corporate analysis and as used for market analysis. Market analysts focus on net income and earnings per share, on the expectation that changes to these numbers will lead to short-term changes to the stock price. Corporate analysts rely much more on financial position than current income numbers.

The authors also discuss circumstances where accounting describes the situation well, and where it doesn't. For example, financial statements are most useful when most profits are to come from the operations of a going-concern and there is heavy regulation limiting management leeway in the accounting assumptions. On the other hand, accounting is not so useful when a large portion of profits are to result from asset sales, imaginative financial techniques are employed, and managements throughout the industry make different accounting choices.

Saturday, April 30, 2011

Friday, April 29, 2011

Chatting Messenger

It's the last Friday of the month, so Frank (author of value site frankvoisin.com) and I are chatting messenger, where we discuss stories from the web that caught our interest:

Frank: Check out AGX. Tons of cash on hand. Sort of a weird conglomerate structure, but very little debt.

Saj: I've written about it here

Frank: Dammit, Saj, I swear you've looked at 98% of public companies.

Saj: Just the ones with high cash to debt balances...I'm no match for Cramer!

Frank: Can you imagine if you were on that show? Cramer would be screaming and making cow sound effects, and then they'd cut to you, and you'd be totally calm and say something about a company's fundamentals.

Saj: And I'd be off the show at the first commercial break. "Sorry, but when we cut to you, our ratings drop 50%"

Frank: "Yeah, can u at least 'moo' or something? Our research indicates animal noises raise viewer interest levels and strengthen our relationships with advertisers"

Saj: So salesforce.com is now trading at a P/E of 300!

Frank: Seems pretty fair.

Saj: Looks like the late 90's are back...any company with a "dot com" in the name is worth 5 times what it would otherwise be worth.

Frank: And another 5 times that that if they are related to "cloud computing" in any way.

Saj: To be fair, the guy in this video makes a pretty good case for owning shares at the current price.

Saj: Chinese reverse-takeover (RTO) stocks continue to take a beating.

Frank: HQS shows us you don't even need to be an RTO to have those problems, as an independent director resigned after claiming management was stalling him as he had "difficulties in verifying information relating to company accounts and customer positions".

Saj: That's pretty bad on the auditor, which is a fairly sizable firm, if "company accounts" are in question.

Frank: People are always saying the auditor can't prevent fraud, but at the very least can't they verify that the cash account is for real??

Saj: Seriously! It's like they spend all their time getting to really specific inventory numbers, or confirming whether the depreciation method conforms to GAAP, when what we'd really like to know is whether the bank balance exists!

Frank: "Are you straight line or accelerating your depreciation of that mirage?"

Saj: We should be allowed to ask auditors questions. "What is your process for verifying cash balances?"

Frank: As much as short sellers get a bad rap, thank God for them. If short-selling were outlawed, as my lawmakers would like, we'd still be thinking some of these stocks look like good value, because the SEC certainly wouldn't uncover these frauds.

Frank: Check out AGX. Tons of cash on hand. Sort of a weird conglomerate structure, but very little debt.

Saj: I've written about it here

Frank: Dammit, Saj, I swear you've looked at 98% of public companies.

Saj: Just the ones with high cash to debt balances...I'm no match for Cramer!

Frank: Can you imagine if you were on that show? Cramer would be screaming and making cow sound effects, and then they'd cut to you, and you'd be totally calm and say something about a company's fundamentals.

Saj: And I'd be off the show at the first commercial break. "Sorry, but when we cut to you, our ratings drop 50%"

Frank: "Yeah, can u at least 'moo' or something? Our research indicates animal noises raise viewer interest levels and strengthen our relationships with advertisers"

Saj: So salesforce.com is now trading at a P/E of 300!

Frank: Seems pretty fair.

Saj: Looks like the late 90's are back...any company with a "dot com" in the name is worth 5 times what it would otherwise be worth.

Frank: And another 5 times that that if they are related to "cloud computing" in any way.

Saj: To be fair, the guy in this video makes a pretty good case for owning shares at the current price.

Saj: Chinese reverse-takeover (RTO) stocks continue to take a beating.

Frank: HQS shows us you don't even need to be an RTO to have those problems, as an independent director resigned after claiming management was stalling him as he had "difficulties in verifying information relating to company accounts and customer positions".

Saj: That's pretty bad on the auditor, which is a fairly sizable firm, if "company accounts" are in question.

Frank: People are always saying the auditor can't prevent fraud, but at the very least can't they verify that the cash account is for real??

Saj: Seriously! It's like they spend all their time getting to really specific inventory numbers, or confirming whether the depreciation method conforms to GAAP, when what we'd really like to know is whether the bank balance exists!

Frank: "Are you straight line or accelerating your depreciation of that mirage?"

Saj: We should be allowed to ask auditors questions. "What is your process for verifying cash balances?"

Frank: As much as short sellers get a bad rap, thank God for them. If short-selling were outlawed, as my lawmakers would like, we'd still be thinking some of these stocks look like good value, because the SEC certainly wouldn't uncover these frauds.

Thursday, April 28, 2011

Danier Leather: Cheap And Accretive

Danier Leather (DL) is a vertically integrated designer, manufacturer and retailer of leather apparel and accessories. The company trades at a price to book value of about 0.75 and a P/E under 9 despite a healthy balance sheet.

Danier has a market capitalization of $60 million, but has generated more than $40 million of operating cash flow over the last four years. Because the company kept capital spending to less than $4 million in each of the last four years, most of this money accrued directly to shareholders.

Last year, the company spent more than $9 million buying back shares. This represents about 15% of the company's current market cap! In a particularly shrewd move, the company bought back a large number of shares via a Dutch Auction last year when the shares traded at about half their current level.

Currently, the company sits on $30 million worth of cash against no debt. The company should be eligible to buy back another 10% of its shares in just a few days, should it decide to continue along the path of buying back its shares, which would be consistent with its history of buybacks. This would have the effect of either pushing up the share price or lowering the company's P/E and P/B ratios even further.

But the perfect investment this is not, as there are some risks to the downside. For one thing, it has been a very profitable year for the company. While that's a good thing, investors should not rely solely on current earnings in calculating a company's earnings power. This was Danier's most profitable year since 2002, so counting on these profits as the new normal going forward may be a bit optimistic. Market forces (including competition, cost pressures etc.) could bring profits lower; they certainly have in the past.

Another potential drawback for shareholders is the company's dual-class share structure. This has allowed an ownership group to control the company without putting in the capital requisite with that level of influence. This structure results in a misalignment of incentives. It also makes it harder to oust management if it were to take actions that are not shareholder friendly.

Finally, this company has had quite an embattled history. It attempted and failed at a costly expansion plan, and managed to irk a few shareholders resulting in a costly lawsuit. While expensive, those incidents are now in the past and have already been paid for; but investors should note that the same management team is still in place, and so if they haven't learned any lessons, similar problems could cost shareholders in the future.

Disclosure: None

Danier has a market capitalization of $60 million, but has generated more than $40 million of operating cash flow over the last four years. Because the company kept capital spending to less than $4 million in each of the last four years, most of this money accrued directly to shareholders.

Last year, the company spent more than $9 million buying back shares. This represents about 15% of the company's current market cap! In a particularly shrewd move, the company bought back a large number of shares via a Dutch Auction last year when the shares traded at about half their current level.

Currently, the company sits on $30 million worth of cash against no debt. The company should be eligible to buy back another 10% of its shares in just a few days, should it decide to continue along the path of buying back its shares, which would be consistent with its history of buybacks. This would have the effect of either pushing up the share price or lowering the company's P/E and P/B ratios even further.

But the perfect investment this is not, as there are some risks to the downside. For one thing, it has been a very profitable year for the company. While that's a good thing, investors should not rely solely on current earnings in calculating a company's earnings power. This was Danier's most profitable year since 2002, so counting on these profits as the new normal going forward may be a bit optimistic. Market forces (including competition, cost pressures etc.) could bring profits lower; they certainly have in the past.

Another potential drawback for shareholders is the company's dual-class share structure. This has allowed an ownership group to control the company without putting in the capital requisite with that level of influence. This structure results in a misalignment of incentives. It also makes it harder to oust management if it were to take actions that are not shareholder friendly.

Finally, this company has had quite an embattled history. It attempted and failed at a costly expansion plan, and managed to irk a few shareholders resulting in a costly lawsuit. While expensive, those incidents are now in the past and have already been paid for; but investors should note that the same management team is still in place, and so if they haven't learned any lessons, similar problems could cost shareholders in the future.

Disclosure: None

Wednesday, April 27, 2011

Jewett Cameron: Buybacks Pay Off

About one year ago, a company by the name of Jewett Cameron was brought up on this site as a potential value investment. At that time, the stock traded around $7/share, but over the last few weeks it has approached $11/share, offering investors the opportunity to exit at a return of approximately 50%.

Of course, there many stocks that have generated this kind of return (or more) in the last year. But what made Jewett a terrific investment was the limited downside risk to investors. That is, even if the economy or the market tanked, investors would likely have been protected. This is something you likely cannot say about the vast majority of securities that have returned 50% in the last year. If we look at some of the key elements that made Jewett's stock a low-risk, high-return type of investment, it can perhaps help us identify stocks that are undervalued right now:

1) Despite depressed earnings as a result of the recession, the company's P/E was under 10

ROE averaged 15% over the last 5 years

2) The company traded for its book value, despite strong ROE (above) and large land amounts carried at historical cost

3) Management had been in place for 25 years, and held a significant stake in the company relative to his salary

4) The company had no debt but lots of cash

Notably absent from these attributes is a "story" of why the shares should rise (predicting future market sentiment on a particular stock is practically impossible) and a known catalyst event that is expected to vault the stock upwards (if a catalyst is known, it's usually too late to buy the shares).

There's nothing overly complex about these attributes. All they signify is that the company was cheap and solvent, generated strong returns on capital, and had an experienced management team with incentives that were aligned with those of shareholders. And that's really all you need!

Disclosure: None

Of course, there many stocks that have generated this kind of return (or more) in the last year. But what made Jewett a terrific investment was the limited downside risk to investors. That is, even if the economy or the market tanked, investors would likely have been protected. This is something you likely cannot say about the vast majority of securities that have returned 50% in the last year. If we look at some of the key elements that made Jewett's stock a low-risk, high-return type of investment, it can perhaps help us identify stocks that are undervalued right now:

1) Despite depressed earnings as a result of the recession, the company's P/E was under 10

ROE averaged 15% over the last 5 years

2) The company traded for its book value, despite strong ROE (above) and large land amounts carried at historical cost

3) Management had been in place for 25 years, and held a significant stake in the company relative to his salary

4) The company had no debt but lots of cash

Notably absent from these attributes is a "story" of why the shares should rise (predicting future market sentiment on a particular stock is practically impossible) and a known catalyst event that is expected to vault the stock upwards (if a catalyst is known, it's usually too late to buy the shares).

There's nothing overly complex about these attributes. All they signify is that the company was cheap and solvent, generated strong returns on capital, and had an experienced management team with incentives that were aligned with those of shareholders. And that's really all you need!

Disclosure: None

Tuesday, April 26, 2011

Orsus Xelent: Mistakes From Which To Learn

One and a half years ago, Orsus Xelent (ORS) was brought up on this site as a potential stock idea. Despite the numerous risks cited in that article, this author went ahead and invested good money in that company. The results were bad, as the stock has fallen by about 80% since that article. Perhaps by looking at what went wrong, it will be possible to avoid similar such mistakes in the future.

The first risk outlined in the article had to do with Orsus' customer concentration. Specifically, this distributor concentration led to a huge receivable balance on Orsus' balance sheet. The stock traded at a massive discount to net current assets, but this receivable balance was the largest component of the company's current assets. Unfortunately, this customer has been unable to make good on its obligations, and Orsus has now written down much of this balance.

Because of the size of the receivable due from this customer, Orsus did insure a large portion of it. Unfortunately, it did not insure enough of the receivable, as the write-down now brings the company to a negative equity position. In other words, the discount to net assets at which this company traded is not only gone, but the company's obligations now outnumber its assets! So while the margin of safety looked large numerically, it was in fact quite weak because it was dependent on the ability of a single customer to pay what it owed, and that didn't happen. Investors would do well to avoid companies heavily reliant on just one or two customers.

Another warning sign was that the company's former CEO was selling his shares at a rather frantic pace. Insider sales are often difficult to interpret, as insiders must often sell stock to lower their own risk (diversification) or to obtain/maintain the lavish lifestyles by which many managers are seduced. In this case, however, the pace of the sales was so strong (resulting in price pressure on the stock, which no seller would want to do unless he was very motivated) that maybe I should have gotten a clue.

But despite these adverse occurrences, I could have sold this stock for only a small loss. But I believe I instead fell victim to loss aversion bias, whereby I held out hope for a profit in order to avoid realizing a loss. Had I encountered this company a year after I did, I don't think I would have been interested in purchasing shares due to the company's inability to collect its receivables over this period. Nevertheless, I continued to hold the stock, which was a serious error in judgment that I believe is explained by this bias.

Unfortunately, knowing about this bias was not enough to prevent me from falling victim to it. Hopefully, having learned the lesson the hard way will save me from this error in the future. I hope this is a stock most readers avoided; and if they didn't, that they sold at a profit (which was possible) or at only a small loss.

Disclosure: None

The first risk outlined in the article had to do with Orsus' customer concentration. Specifically, this distributor concentration led to a huge receivable balance on Orsus' balance sheet. The stock traded at a massive discount to net current assets, but this receivable balance was the largest component of the company's current assets. Unfortunately, this customer has been unable to make good on its obligations, and Orsus has now written down much of this balance.

Because of the size of the receivable due from this customer, Orsus did insure a large portion of it. Unfortunately, it did not insure enough of the receivable, as the write-down now brings the company to a negative equity position. In other words, the discount to net assets at which this company traded is not only gone, but the company's obligations now outnumber its assets! So while the margin of safety looked large numerically, it was in fact quite weak because it was dependent on the ability of a single customer to pay what it owed, and that didn't happen. Investors would do well to avoid companies heavily reliant on just one or two customers.

Another warning sign was that the company's former CEO was selling his shares at a rather frantic pace. Insider sales are often difficult to interpret, as insiders must often sell stock to lower their own risk (diversification) or to obtain/maintain the lavish lifestyles by which many managers are seduced. In this case, however, the pace of the sales was so strong (resulting in price pressure on the stock, which no seller would want to do unless he was very motivated) that maybe I should have gotten a clue.

But despite these adverse occurrences, I could have sold this stock for only a small loss. But I believe I instead fell victim to loss aversion bias, whereby I held out hope for a profit in order to avoid realizing a loss. Had I encountered this company a year after I did, I don't think I would have been interested in purchasing shares due to the company's inability to collect its receivables over this period. Nevertheless, I continued to hold the stock, which was a serious error in judgment that I believe is explained by this bias.

Unfortunately, knowing about this bias was not enough to prevent me from falling victim to it. Hopefully, having learned the lesson the hard way will save me from this error in the future. I hope this is a stock most readers avoided; and if they didn't, that they sold at a profit (which was possible) or at only a small loss.

Disclosure: None

Monday, April 25, 2011

Bassett Furniture: Asset Catalysts

Bassett Furniture (BSET) is a vertically integrated furniture company, as it imports, manufactures, wholesales and distributes a range of furniture. The company was profitable during the housing bubble, lost money for a while following the housing crash, and is now operating pretty close to break-even. But for value investors, it's not the earnings that are interesting, but the catalyst events surrounding some of the company's assets.

Bassett trades for $95 million, but has a deal in place (that is expected to close by the end of this month) to sell a company in which it has a minority interest for $74 million! This sale will produce a gain, which is subject to tax, but the company notes that it has "net operating loss carryforwards of [$18 million] that can be utilized to offset the taxes on the gain." In addition, the buyer will place $7 million in an escrow account that Bassett could receive over the next three years if no unexpected contingencies arise out of the company being sold.

In addition, Bassett has current assets of $83 million, long-term investments (money market and bonds) of $15 million, another minority investment carried at $5 million (equity method), and many tens of millions of dollars of retail real estate (including its own locations and locations it leases to licensees who are wholesale customers of Bassett), versus total liabilities of $83 million.

Of course, there are some risks with this type of investment. The most obvious is that the proposed deal may not close. But even if it doesn't, investors have a pretty good idea of what that minority investment is worth, which should act as a margin of safety.

But perhaps the biggest risk is what the company will do with all that money. Management didn't exactly narrow it down for shareholders when it stated it may use the money for "the retirement of debt and certain other long-term obligations, the settlement of various obligations related to closed stores and idle facilities, restructuring licensee debt, paying a dividend, judiciously funding expansion of our Company-owned store network, and/or funding stock buybacks and/or funding any potential future working capital needs."

While such a wide range of possibilities may be a bit scary for value investors, the company does have a history of paying out special dividends and buying back shares when it has extra cash. Unfortunately, management may only have done this because it had a gun to its head, thanks to activist shareholders who challenged the company's capital allocation. Management would probably rather grow the company than serve shareholders, as the company's CEO owns less than a million dollars worth of Bassett shares, but got paid almost half a million dollars last year.

On the other hand, management has not been taking wanton risks as of late to grow the company at the risk of profitability; the company has been closing the least profitable stores, and capex has been consistently below depreciation as the company has limited spending to store upgrades/refreshes rather than unjustified expansion. But management does appear to be pleased with the results of some new-concept stores it has been testing, so the possibility is there that management will use the bulk of this cash inflow to fund a growth program with uncertain results.

As Bassett shrinks down to its most profitable stores, it may be on the verge of returning to profitability. At the same time, it is likely to receive a major cash injection that the company may use to benefit shareholders. Value investors who believe this management team to be prudent may find this a stock worthy of investment, but those who don't will want to stay away.

Disclosure: None

Bassett trades for $95 million, but has a deal in place (that is expected to close by the end of this month) to sell a company in which it has a minority interest for $74 million! This sale will produce a gain, which is subject to tax, but the company notes that it has "net operating loss carryforwards of [$18 million] that can be utilized to offset the taxes on the gain." In addition, the buyer will place $7 million in an escrow account that Bassett could receive over the next three years if no unexpected contingencies arise out of the company being sold.

In addition, Bassett has current assets of $83 million, long-term investments (money market and bonds) of $15 million, another minority investment carried at $5 million (equity method), and many tens of millions of dollars of retail real estate (including its own locations and locations it leases to licensees who are wholesale customers of Bassett), versus total liabilities of $83 million.

Of course, there are some risks with this type of investment. The most obvious is that the proposed deal may not close. But even if it doesn't, investors have a pretty good idea of what that minority investment is worth, which should act as a margin of safety.

But perhaps the biggest risk is what the company will do with all that money. Management didn't exactly narrow it down for shareholders when it stated it may use the money for "the retirement of debt and certain other long-term obligations, the settlement of various obligations related to closed stores and idle facilities, restructuring licensee debt, paying a dividend, judiciously funding expansion of our Company-owned store network, and/or funding stock buybacks and/or funding any potential future working capital needs."

While such a wide range of possibilities may be a bit scary for value investors, the company does have a history of paying out special dividends and buying back shares when it has extra cash. Unfortunately, management may only have done this because it had a gun to its head, thanks to activist shareholders who challenged the company's capital allocation. Management would probably rather grow the company than serve shareholders, as the company's CEO owns less than a million dollars worth of Bassett shares, but got paid almost half a million dollars last year.

On the other hand, management has not been taking wanton risks as of late to grow the company at the risk of profitability; the company has been closing the least profitable stores, and capex has been consistently below depreciation as the company has limited spending to store upgrades/refreshes rather than unjustified expansion. But management does appear to be pleased with the results of some new-concept stores it has been testing, so the possibility is there that management will use the bulk of this cash inflow to fund a growth program with uncertain results.

As Bassett shrinks down to its most profitable stores, it may be on the verge of returning to profitability. At the same time, it is likely to receive a major cash injection that the company may use to benefit shareholders. Value investors who believe this management team to be prudent may find this a stock worthy of investment, but those who don't will want to stay away.

Disclosure: None

Sunday, April 24, 2011

The Aggressive Conservative Investor: Chapter 6

Martin Whitman founded Third Avenue Value Fund some twenty years ago. Over that time period, the fund has beaten the returns of the S&P 500 by several points annually. In The Aggressive Conservative Investor, Whitman collaborates with Martin Shubik to discuss a concept that they call "safe and cheap" investing.

The authors briefly discuss many of the disclosures public companies must release by SEC requirement, including financial statements and their notes. The usefulness of this paper trail of documents will vary by industry. For example, for a steady dividend-payer in a mature industry, more information will probably be released than the investor needs; however, for a miner or real estate company, GAAP financials are not as useful in determining a company's value.

For the investor to fully fathom the usefulness of these public disclosures, the authors argue it is useful to understand how they are created. For one thing, the lawyers and accountants who prepare many of the disclosure documents have no desire to risk their reputations on a third party (i.e. the company's management). As such, they are rather meticulous in making sure they disclose what they should, and are honest in doing so. Though frauds do occur, the authors believe they are few and far between, especially when compared with normal commercial transactions (where parties must always worry about the truthfulness of the party with which they are transacting).

Investors are also encouraged to obtain copies of the forms and mandated regulations required for filling them out. This will give investors a good idea of what those who fill out the disclosures must go through, and will therefore help the investor understand why a disclosure is laid out as such.

These disclosures also help identify which companies are not worthy of investment no matter what the price! Though many believe that every security is worth something at a low enough price, the authors argue against this line of thought. Some securities are too junior compared to the obligations of the company, and some managements are so egregious in their treatment of shareholders, that some securities should be discarded outright based on their disclosures.

Finally, it's important to recognize what's not contained in the disclosures. Internal budgets, management disagreements, marketing plans and other such matters in which shareholders might be interested are not normally disclosed. Often, projections, budgets and asset appraisals can be used for stock manipulation, so in some cases it is better that such "soft" details are left out. Nevertheless, the authors argue that in many cases these disclosures are so useful that they are all the investor will need to form an opinion of whether a security is worthy of investment.

The authors briefly discuss many of the disclosures public companies must release by SEC requirement, including financial statements and their notes. The usefulness of this paper trail of documents will vary by industry. For example, for a steady dividend-payer in a mature industry, more information will probably be released than the investor needs; however, for a miner or real estate company, GAAP financials are not as useful in determining a company's value.

For the investor to fully fathom the usefulness of these public disclosures, the authors argue it is useful to understand how they are created. For one thing, the lawyers and accountants who prepare many of the disclosure documents have no desire to risk their reputations on a third party (i.e. the company's management). As such, they are rather meticulous in making sure they disclose what they should, and are honest in doing so. Though frauds do occur, the authors believe they are few and far between, especially when compared with normal commercial transactions (where parties must always worry about the truthfulness of the party with which they are transacting).

Investors are also encouraged to obtain copies of the forms and mandated regulations required for filling them out. This will give investors a good idea of what those who fill out the disclosures must go through, and will therefore help the investor understand why a disclosure is laid out as such.

These disclosures also help identify which companies are not worthy of investment no matter what the price! Though many believe that every security is worth something at a low enough price, the authors argue against this line of thought. Some securities are too junior compared to the obligations of the company, and some managements are so egregious in their treatment of shareholders, that some securities should be discarded outright based on their disclosures.

Finally, it's important to recognize what's not contained in the disclosures. Internal budgets, management disagreements, marketing plans and other such matters in which shareholders might be interested are not normally disclosed. Often, projections, budgets and asset appraisals can be used for stock manipulation, so in some cases it is better that such "soft" details are left out. Nevertheless, the authors argue that in many cases these disclosures are so useful that they are all the investor will need to form an opinion of whether a security is worthy of investment.

Saturday, April 23, 2011

The Aggressive Conservative Investor: Chapter 5

Martin Whitman founded Third Avenue Value Fund some twenty years ago. Over that time period, the fund has beaten the returns of the S&P 500 by several points annually. In The Aggressive Conservative Investor, Whitman collaborates with Martin Shubik to discuss a concept that they call "safe and cheap" investing.

The authors argue that there is risk in every investment. No amount of research can completely eliminate risk. Even if the investor does an absolutely thorough job analyzing a company, his analysis could be wrong, he could misappraise management, future unexpected events could occur, and/or the market may never recognize a company's true value. But using the techniques described in the book, investors should seek to tip the scales of the risk-reward ratio in their favour.

Most investors judge a stock's risk by the quality of the issuer. A well-known company, judged by others to be a quality issuer, is often considered a low-risk security by investors. The problem with this line of thinking, according to the authors, is that the fact that the company is a "quality issuer" would already be ingrained in the stock's price. As such, investors often pay a premium for such issues.

But what is considered a quality issuer changes over time. The authors describe a number of examples through the decades where quality companies have inevitably declined in prominence over time. These stocks in effect suffer a double-whammy of negative returns, as the companies decline in both earnings and in price multiples (e.g. their P/E ratios) as they lose their "quality" status.

Nevertheless, for investors will little knowledge of the market and a weak understanding of companies, a diversified quality-issue portfolio is likely appropriate. But for investors who are willing to take the time to understand a company, the authors argue that the issuer's quality is only one of three factors influencing risk, with the other two being price and financial position.

Smart investors with a deep understanding of a company seek to reduce risk by purchasing when the price is low (relative to the investor's estimate of the company's value). In this view of risk, risk actually reduces as upside potential increases. This is in contrast to the prevailing view in the finance industry, where conventional wisdom suggests that only by taking more risk can an investor achieve higher returns.

Finally, the third element of risk is financial position. Even the safest investment of all (e.g. US treasuries) can become a casino-style gamble if financed with 95% leverage. Some value investments can take years to play out, and therefore a strong financial position is important to be able to outlast the bad times.

The authors argue that there is risk in every investment. No amount of research can completely eliminate risk. Even if the investor does an absolutely thorough job analyzing a company, his analysis could be wrong, he could misappraise management, future unexpected events could occur, and/or the market may never recognize a company's true value. But using the techniques described in the book, investors should seek to tip the scales of the risk-reward ratio in their favour.

Most investors judge a stock's risk by the quality of the issuer. A well-known company, judged by others to be a quality issuer, is often considered a low-risk security by investors. The problem with this line of thinking, according to the authors, is that the fact that the company is a "quality issuer" would already be ingrained in the stock's price. As such, investors often pay a premium for such issues.

But what is considered a quality issuer changes over time. The authors describe a number of examples through the decades where quality companies have inevitably declined in prominence over time. These stocks in effect suffer a double-whammy of negative returns, as the companies decline in both earnings and in price multiples (e.g. their P/E ratios) as they lose their "quality" status.

Nevertheless, for investors will little knowledge of the market and a weak understanding of companies, a diversified quality-issue portfolio is likely appropriate. But for investors who are willing to take the time to understand a company, the authors argue that the issuer's quality is only one of three factors influencing risk, with the other two being price and financial position.

Smart investors with a deep understanding of a company seek to reduce risk by purchasing when the price is low (relative to the investor's estimate of the company's value). In this view of risk, risk actually reduces as upside potential increases. This is in contrast to the prevailing view in the finance industry, where conventional wisdom suggests that only by taking more risk can an investor achieve higher returns.

Finally, the third element of risk is financial position. Even the safest investment of all (e.g. US treasuries) can become a casino-style gamble if financed with 95% leverage. Some value investments can take years to play out, and therefore a strong financial position is important to be able to outlast the bad times.

Friday, April 22, 2011

The Aggressive Conservative Investor: Chapter 4

Martin Whitman founded Third Avenue Value Fund some twenty years ago. Over that time period, the fund has beaten the returns of the S&P 500 by several points annually. In The Aggressive Conservative Investor, Whitman collaborates with Martin Shubik to discuss a concept that they call "safe and cheap" investing.

The authors now take up the topic of modern portfolio theory, where it is assumed that prices properly reflect information relevant to a stock. The following passage from a textbook is critiqued:

"There are thousands of professional fundamental security analysts at work in the United States . . . As a result of the efforts of this army of professional fundamental analysts, the price of any publicly listed and traded security represents the best estimate available at that moment of the intrinsic value of that security. In fact, the fundamental analysts do such a good job, there is no reason for anyone who is not a full time professional to bother with fundamental analysis."

The authors flatly disagree with the above statement. They even go so far as to say that there aren't many competent analysts out there, certainly not enough to be able to render every security to its proper price. This is particularly true because many of the analysts out there are looking to determine where the stock price will go, rather than focusing on the fundamental value of the business.

The authors do argue that the market is efficient in some sense. For those who attempt to generate short-term returns, for example, empirical data suggest a "random walk" to prices. Furthermore, certain markets, such as the high-grade (low yield) corporate bond market are pretty efficient in the authors' opinions. However, the authors argue that it has not been proven that all investors interpret the public evidence correctly such that long-term gains in equities and other instruments cannot be realized due to market mis-pricings.

The authors now take up the topic of modern portfolio theory, where it is assumed that prices properly reflect information relevant to a stock. The following passage from a textbook is critiqued:

"There are thousands of professional fundamental security analysts at work in the United States . . . As a result of the efforts of this army of professional fundamental analysts, the price of any publicly listed and traded security represents the best estimate available at that moment of the intrinsic value of that security. In fact, the fundamental analysts do such a good job, there is no reason for anyone who is not a full time professional to bother with fundamental analysis."

The authors flatly disagree with the above statement. They even go so far as to say that there aren't many competent analysts out there, certainly not enough to be able to render every security to its proper price. This is particularly true because many of the analysts out there are looking to determine where the stock price will go, rather than focusing on the fundamental value of the business.

The authors do argue that the market is efficient in some sense. For those who attempt to generate short-term returns, for example, empirical data suggest a "random walk" to prices. Furthermore, certain markets, such as the high-grade (low yield) corporate bond market are pretty efficient in the authors' opinions. However, the authors argue that it has not been proven that all investors interpret the public evidence correctly such that long-term gains in equities and other instruments cannot be realized due to market mis-pricings.

Thursday, April 21, 2011

The More You Know, The Much More You Think You Know

In a previous post, we saw how humans appear to have an overconfidence bias, and how that can play havoc on financial forecast estimations. What is not immediately clear, however, is the increasing role overconfidence plays the more knowledge one acquires. That is, as expertise rises, so does overconfidence, resulting in the fact that the people with the most knowledge are likely to be the most miscalibrated, which can result in detrimental effects.

But knowledge alone does not doom someone into being overconfident. James Montier argues that it's a lack of feedback that pushes people to be overconfident. To demonstrate this, Montier cites a study performed by Scott Plous that compares the calibration of weathermen against that of doctors. Weathermen were asked to predict the weather, while doctors were asked to diagnose patients (based on case notes). Both were asked to provide confidence intervals, so that their calibrations could be measured.

Interestingly, weatherman were well calibrated, while doctors were very poorly calibrated. Montier argues that this is because weather forecasters benefit from the fact that they receive immediate evidence of their abilities as forecasters, while doctors do not.

While one may be inclined to believe that financial analysts should be like weathermen in that they can see whether their forecasts came true, similar calibration tests appear to show that analysts are calibrated to a similar extent as doctors! As a result, the industry is glowing with overconfidence. Further testing confirmed the opening hypothesis: experts in finance are more overconfident than lay people, as they apply too narrow a band around their estimates as compared to the general public.

But knowledge alone does not doom someone into being overconfident. James Montier argues that it's a lack of feedback that pushes people to be overconfident. To demonstrate this, Montier cites a study performed by Scott Plous that compares the calibration of weathermen against that of doctors. Weathermen were asked to predict the weather, while doctors were asked to diagnose patients (based on case notes). Both were asked to provide confidence intervals, so that their calibrations could be measured.

Interestingly, weatherman were well calibrated, while doctors were very poorly calibrated. Montier argues that this is because weather forecasters benefit from the fact that they receive immediate evidence of their abilities as forecasters, while doctors do not.

While one may be inclined to believe that financial analysts should be like weathermen in that they can see whether their forecasts came true, similar calibration tests appear to show that analysts are calibrated to a similar extent as doctors! As a result, the industry is glowing with overconfidence. Further testing confirmed the opening hypothesis: experts in finance are more overconfident than lay people, as they apply too narrow a band around their estimates as compared to the general public.

Wednesday, April 20, 2011

Hart Stores: Cheap, But Growing

Hart Stores (HIS) is a department store retailer with 92 locations under the "Hart" and "Bargain Giant" banners. The retailer has maintained profitability throughout the economic downturn, and yet it trades for less than its net current assets. In Hart's last four fiscal years, the company has generated $16 million of operating income. But today, its market cap is just $20 million, giving it a price to book ratio of just over 0.4.

The problem with Hart is not so much its historical earnings but rather the trend of those earnings. Even before the recession, margins were on the decline, suggesting the company was having trouble competing with better assorted/priced other retailers. This has occurred despite the company's claims that it has "a dominant position in many of the communities it serves". Things have now deteriorated to the point where it is in doubt as to whether the company will have turned a profit last year; fourth quarter results should be out in a few days.

But the numbers likely underestimate the problems at this retailer, as the company has been able to benefit from a strong Canadian dollar. As the company procures a lot of its products from the US in US dollars, it sells its products to Canadians in strong Canadian dollars. This is likely helping profits, and yet the financials continue to deteriorate, suggesting the company is having a lot of difficulty competing. What would happen if the currency trend were to reverse?

Even though operations are on the decline, the company is pushing ahead with expansion plans. For many investors, this likely appears to be a risky strategy; normally, value investors like cheap companies that are growing, but only if they are growing profitably. Hart's strategy appears risky, considering that the company's existing stores already appear in trouble.

Unfortunately, investors really are outsiders when it comes to this company. For better of for worse, the Hart family controls the company. As discussed before, sometimes family business owners have different priorities than maximizing shareholder value. These priorities can sometimes lead to an imperative to grow/invest in a business even if the more prudent action might be to return cash to shareholders, who can then allocate capital to investments with better risk/reward profiles.

Of course, if the Harts (who as a team occupy the Chairman, CEO, President, and three board of director positions) can turn this thing around, shareholders will be greatly rewarded. Unfortunately, there is no indication (at least to outside shareholders) that this is either possible or plausible.

Disclosure: None

The problem with Hart is not so much its historical earnings but rather the trend of those earnings. Even before the recession, margins were on the decline, suggesting the company was having trouble competing with better assorted/priced other retailers. This has occurred despite the company's claims that it has "a dominant position in many of the communities it serves". Things have now deteriorated to the point where it is in doubt as to whether the company will have turned a profit last year; fourth quarter results should be out in a few days.

But the numbers likely underestimate the problems at this retailer, as the company has been able to benefit from a strong Canadian dollar. As the company procures a lot of its products from the US in US dollars, it sells its products to Canadians in strong Canadian dollars. This is likely helping profits, and yet the financials continue to deteriorate, suggesting the company is having a lot of difficulty competing. What would happen if the currency trend were to reverse?

Even though operations are on the decline, the company is pushing ahead with expansion plans. For many investors, this likely appears to be a risky strategy; normally, value investors like cheap companies that are growing, but only if they are growing profitably. Hart's strategy appears risky, considering that the company's existing stores already appear in trouble.

Unfortunately, investors really are outsiders when it comes to this company. For better of for worse, the Hart family controls the company. As discussed before, sometimes family business owners have different priorities than maximizing shareholder value. These priorities can sometimes lead to an imperative to grow/invest in a business even if the more prudent action might be to return cash to shareholders, who can then allocate capital to investments with better risk/reward profiles.

Of course, if the Harts (who as a team occupy the Chairman, CEO, President, and three board of director positions) can turn this thing around, shareholders will be greatly rewarded. Unfortunately, there is no indication (at least to outside shareholders) that this is either possible or plausible.

Disclosure: None

Tuesday, April 19, 2011

Industry ROIC

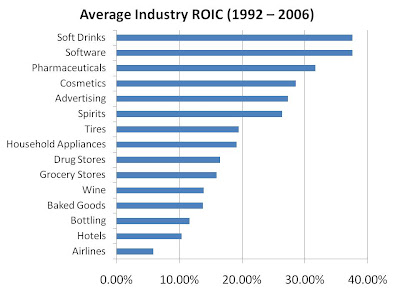

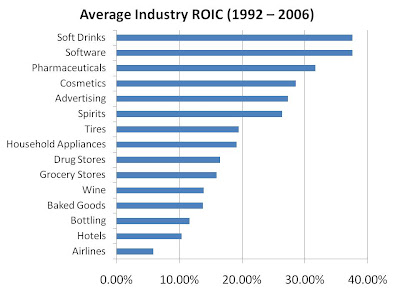

One of the most important determinants of whether a company makes for a good long-term investment is the industry within which it operates. We've discussed the boom and bust nature of the housing industry, the generous margins garnered by the soft-drink industry giants, and reasons why airlines make for poor long-term investments. But on the average, what do industry returns look like?

Harvard Professor Michael Porter, using data from Standard and Poor's as well as Compustat, has calculated the profitabilites of various industries over the 1992-2006 period, some of which are shown below:

Clearly, there is high variability in returns on capital by industry. Average industry ROIC in the US was calculated at 14.9% by Porter, demonstrating that some industries are clearly extremely profitable, while others destroy capital.

Does this mean you shouldn't own a company whose industry returns fall below the average ROIC? Absolutely not! Within industries, returns may also be highly variable, in the case where one or two companies have differentiated themselves or are low-cost producers that generate consistent industry-beating returns. Furthermore, even companies with meager returns can trade at such large discounts to book that returns on the market price of equity are quite high. But you may still want to stay away from the airline industry!

Harvard Professor Michael Porter, using data from Standard and Poor's as well as Compustat, has calculated the profitabilites of various industries over the 1992-2006 period, some of which are shown below:

Clearly, there is high variability in returns on capital by industry. Average industry ROIC in the US was calculated at 14.9% by Porter, demonstrating that some industries are clearly extremely profitable, while others destroy capital.

Does this mean you shouldn't own a company whose industry returns fall below the average ROIC? Absolutely not! Within industries, returns may also be highly variable, in the case where one or two companies have differentiated themselves or are low-cost producers that generate consistent industry-beating returns. Furthermore, even companies with meager returns can trade at such large discounts to book that returns on the market price of equity are quite high. But you may still want to stay away from the airline industry!

Monday, April 18, 2011

Seeking Alpha Pro Tech

Last time Alpha Pro Tech was discussed on this site (about one year ago), investors were warned to be wary of the company's current earnings because of a one-time spike in revenue. Alpha Pro Tech (APT) makes a range of protective products, and demand for its face mask spiked last year as fears of an H1N1 breakout spread. Now that revenue has dropped back down to normal, however, it appears that the market may have overreacted to the downside, as the stock is down more than 60% since that article and more than 80% from its 2009 peak.

APT now trades at a price to book value of about 0.8, despite profits over the last business cycle that are reasonable compared to invested capital. This gives the investor solid downside protection, as the company approximately trades for its net current assets despite a history of positive net income.

The reason for the low stock price is likely due to low current earnings, as the company barely eked out a profit last quarter. In addition to having to deal with the drop in demand of face masks, the company was recently dealt a blow by its major distributor, which decided to compete with the company on certain products. This distributor represented almost 30% of sales in 2009 (this is a major risk, as previously discussed), but now represents only 14% of the company's sales, which should result in much more stability going forward.

The company also appears to be taking shareholder-friendly steps to get the company back on the right track. It sold its money-losing pet bed business two months ago for its inventory at cost plus Goodwill. When a company trading at a discount to its book value converts assets into cash, it usually reduces the investor's risk. APT has also been consolidating its manufacturing facilities in an attempt to cut costs. Furthermore, perhaps recognizing that the shares are cheap, the company recently increased its share buyback authorization.

But can the company get back to the level of profitability it has shown in the past? There are some reasons to be optimistic. The company's Building Supply segment has quadrupled in revenue since 2007 despite a very weak housing market, and contributed a record $2.4 million to the company's income in 2010. As a result of strong customer response to the company's roofing products, management has increased inventories for this segment in anticipation of even higher sales in 2011. If you slap a 10x multiple on the 2010 figure and add the company's cash balance, this gives a valuation of $29 million, which is what the entire company trades for! From this vantage point, the investor is receiving the other two segments (Infection Control and Protective Apparel), which are historically APT's most profitable segments, for free!

The investor's path to prosperity through this stock is not without risk, however. In many product lines, APT competes with several companies with larger scale and financial clout. Furthermore, management's bonus structure provides clear incentives to grow the company's operating income; attempts to grow profits are not always in the best interests of shareholders, as there is a risk that management will seek to enlarge the company at low rates of return on capital. At the current price, however, the market may be offering shareholders three profitable business lines for the price of one.

Disclosure: Author has a long position in shares of APT

APT now trades at a price to book value of about 0.8, despite profits over the last business cycle that are reasonable compared to invested capital. This gives the investor solid downside protection, as the company approximately trades for its net current assets despite a history of positive net income.

The reason for the low stock price is likely due to low current earnings, as the company barely eked out a profit last quarter. In addition to having to deal with the drop in demand of face masks, the company was recently dealt a blow by its major distributor, which decided to compete with the company on certain products. This distributor represented almost 30% of sales in 2009 (this is a major risk, as previously discussed), but now represents only 14% of the company's sales, which should result in much more stability going forward.

The company also appears to be taking shareholder-friendly steps to get the company back on the right track. It sold its money-losing pet bed business two months ago for its inventory at cost plus Goodwill. When a company trading at a discount to its book value converts assets into cash, it usually reduces the investor's risk. APT has also been consolidating its manufacturing facilities in an attempt to cut costs. Furthermore, perhaps recognizing that the shares are cheap, the company recently increased its share buyback authorization.

But can the company get back to the level of profitability it has shown in the past? There are some reasons to be optimistic. The company's Building Supply segment has quadrupled in revenue since 2007 despite a very weak housing market, and contributed a record $2.4 million to the company's income in 2010. As a result of strong customer response to the company's roofing products, management has increased inventories for this segment in anticipation of even higher sales in 2011. If you slap a 10x multiple on the 2010 figure and add the company's cash balance, this gives a valuation of $29 million, which is what the entire company trades for! From this vantage point, the investor is receiving the other two segments (Infection Control and Protective Apparel), which are historically APT's most profitable segments, for free!

The investor's path to prosperity through this stock is not without risk, however. In many product lines, APT competes with several companies with larger scale and financial clout. Furthermore, management's bonus structure provides clear incentives to grow the company's operating income; attempts to grow profits are not always in the best interests of shareholders, as there is a risk that management will seek to enlarge the company at low rates of return on capital. At the current price, however, the market may be offering shareholders three profitable business lines for the price of one.

Disclosure: Author has a long position in shares of APT

Sunday, April 17, 2011

The Aggressive Conservative Investor: Chapter 3

Martin Whitman founded Third Avenue Value Fund some twenty years ago. Over that time period, the fund has beaten the returns of the S&P 500 by several points annually. In The Aggressive Conservative Investor, Whitman collaborates with Martin Shubik to discuss a concept that they call "safe and cheap" investing.

In this chapter, the authors discuss the importance of price performance to an investor. An argument is made that too many market participants put too great an emphasis on price performance, and not enough emphasis on business performance. But there are a number of reasons why a company's short-term price and long-term business performance can diverge, including:

- changes in stock market levels

- changes in interest rates

- cyclical economic fluctuations

- quarterly (near-term) earnings performance

- dividend changes

The authors do, however, recognize that for some, price performance is of paramount importance. For example, traders who know nothing about the company's business but who focus only on price volatility, trading volumes and previous price movements have no choice but to rely 100% on a security's price movements in making their decisions. At the other extreme, those with a long-term outlook who have a deep knowledge and understanding of the underlying business' value wouldn't place much emphasis at all on the security's price performance, opting instead to rely on their own valuations.

The authors also take issue with the general consensus that has developed with respect to the value that money managers add based on their short-term performance. Because many managers are beaten by the market after fees, it is generally accepted that these managers are useless. But the authors make the point that most managers have requirements such that "beating the market" is not part of, or only a small part of, their mandates. For example, the money manager at an insurance company should not be trying to outperform a bull market, but rather protect his business from being under-capitalized. Furthermore, statistically, even terrific money managers will be beaten by the market over several periods.

In this chapter, the authors discuss the importance of price performance to an investor. An argument is made that too many market participants put too great an emphasis on price performance, and not enough emphasis on business performance. But there are a number of reasons why a company's short-term price and long-term business performance can diverge, including:

- changes in stock market levels

- changes in interest rates

- cyclical economic fluctuations

- quarterly (near-term) earnings performance

- dividend changes

The authors do, however, recognize that for some, price performance is of paramount importance. For example, traders who know nothing about the company's business but who focus only on price volatility, trading volumes and previous price movements have no choice but to rely 100% on a security's price movements in making their decisions. At the other extreme, those with a long-term outlook who have a deep knowledge and understanding of the underlying business' value wouldn't place much emphasis at all on the security's price performance, opting instead to rely on their own valuations.

The authors also take issue with the general consensus that has developed with respect to the value that money managers add based on their short-term performance. Because many managers are beaten by the market after fees, it is generally accepted that these managers are useless. But the authors make the point that most managers have requirements such that "beating the market" is not part of, or only a small part of, their mandates. For example, the money manager at an insurance company should not be trying to outperform a bull market, but rather protect his business from being under-capitalized. Furthermore, statistically, even terrific money managers will be beaten by the market over several periods.

Saturday, April 16, 2011

The Aggressive Conservative Investor: Chapter 2

Martin Whitman founded Third Avenue Value Fund some twenty years ago. Over that time period, the fund has beaten the returns of the S&P 500 by several points annually. In The Aggressive Conservative Investor, Whitman collaborates with Martin Shubik to discuss a concept that they call "safe and cheap" investing.

The authors believe that successful activist investors, creditors and private owners share two common attitudes towards investing that regular investors would do well to internalize. The first concerns their perspective towards losses vs gains. The authors argue that the most successful activists first consider how much they can lose before asking the question of how much they can gain.

The second attitude concerns their perspective of risk. To successful activists, risk is not measured externally (e.g. as a function of price volatility), but rather internally as a function of the quality of the security and its financial position.

This leads the authors to describe a philosophy of investing that they believe leads to superior returns in the long-haul relative to the market. They call it the "Financial-Integrity Approach To Equity Investing". Under this approach, a security may only be considered for purchase if the following four tenets are met:

1) The underlying company has a strong financial position (more important than strong assets is the lack of significant obligations)

2) An honest management and control group

3) A reasonable amount of relevant information about the security is available

4) It is priced below the investor's estimate of net asset value

The authors take care to note that just because a security meets these requirements does not make it suitable for purchase; rather, it must meet all four criteria to be even considered for purchase.

Even though the authors believe an investor following this philosophy will do well, they note that it has several disadvantages. For one thing, it requires a lot of reading and understanding of numerous documents/filings. Furthermore, since the investor is not in a control position, he has no control of the timetable of when he will be in a position to buy/sell the security. Finally, there are only a small subset (many of which are illiquid!) of the market's securities that fit into these criteria.

The authors believe that successful activist investors, creditors and private owners share two common attitudes towards investing that regular investors would do well to internalize. The first concerns their perspective towards losses vs gains. The authors argue that the most successful activists first consider how much they can lose before asking the question of how much they can gain.

The second attitude concerns their perspective of risk. To successful activists, risk is not measured externally (e.g. as a function of price volatility), but rather internally as a function of the quality of the security and its financial position.

This leads the authors to describe a philosophy of investing that they believe leads to superior returns in the long-haul relative to the market. They call it the "Financial-Integrity Approach To Equity Investing". Under this approach, a security may only be considered for purchase if the following four tenets are met:

1) The underlying company has a strong financial position (more important than strong assets is the lack of significant obligations)

2) An honest management and control group

3) A reasonable amount of relevant information about the security is available

4) It is priced below the investor's estimate of net asset value

The authors take care to note that just because a security meets these requirements does not make it suitable for purchase; rather, it must meet all four criteria to be even considered for purchase.

Even though the authors believe an investor following this philosophy will do well, they note that it has several disadvantages. For one thing, it requires a lot of reading and understanding of numerous documents/filings. Furthermore, since the investor is not in a control position, he has no control of the timetable of when he will be in a position to buy/sell the security. Finally, there are only a small subset (many of which are illiquid!) of the market's securities that fit into these criteria.

Friday, April 15, 2011

Risk vs Uncertainty

Humans don't like ambiguity. This is demonstrated in the experiment Hersh Shefrin discusses where subjects are offered either a guaranteed $1000, or a 50/50 chance at $2000. Consistently, fewer than 50% of respondents prefer the gamble for $2000, even though the expected values (i.e. the average value of the result if it were conducted many times) of both offers are the same.

What if the 50/50 odds in the above experiment were instead unknown? This adds even further uncertainty to the situation, and results in even fewer people willing to gamble on the $2000.

Shefrin calls this phenomenon "aversion to ambiguity", and on Wall Street it results in downward pressure on the prices of securities with uncertain outlooks. In order to avoid uncertainty/ambiguity, humans will stay away, even if the odds are favourable (i.e. downside risk is low, upside potential is high).

In his book, Shefrin argues that this ambiguity aversion is the reason for government intervention, even when it is not needed. What would have happened had the government not bailed out the banks? Nobody really knows, but the fact that the outlook was uncertain made the government want to intervene, even at a high cost, in order to avoid the uncertain situation.

As Mohnish Pabrai notes in his book, risk is not the same as uncertainty. Uncertainty can drive down the prices of assets/securities, even if downside risk is low. By capitalizing on situations where uncertainty is high, but risk is low, the investor can put himself in a position to earn above-average returns.

What if the 50/50 odds in the above experiment were instead unknown? This adds even further uncertainty to the situation, and results in even fewer people willing to gamble on the $2000.

Shefrin calls this phenomenon "aversion to ambiguity", and on Wall Street it results in downward pressure on the prices of securities with uncertain outlooks. In order to avoid uncertainty/ambiguity, humans will stay away, even if the odds are favourable (i.e. downside risk is low, upside potential is high).

In his book, Shefrin argues that this ambiguity aversion is the reason for government intervention, even when it is not needed. What would have happened had the government not bailed out the banks? Nobody really knows, but the fact that the outlook was uncertain made the government want to intervene, even at a high cost, in order to avoid the uncertain situation.

As Mohnish Pabrai notes in his book, risk is not the same as uncertainty. Uncertainty can drive down the prices of assets/securities, even if downside risk is low. By capitalizing on situations where uncertainty is high, but risk is low, the investor can put himself in a position to earn above-average returns.

Thursday, April 14, 2011

Xyratex: Growth Company At Value Price?

Xyratex (XRTX) designs and manufactures digital storage solutions and storage process technology. The company can currently be purchased at a price not seen since 2004, when revenues were about one-third of what they are today. The company trades at a P/E of just 2.5, while sporting cash of $98 million against no debt.

The stock has fallen by 40% in just the last three months, as both the company's financial performance and its outlook have been below estimates. If the problems the business faces are short-term in nature, this is the kind of situation where value investors with a long-term view can generate strong returns.

In the early part of 2011, PC sales have been lower than expected, reducing demand for the company's products. One of Xyratex's two segments derives revenues in large part from the capex investments of storage firms, which results in heavy cyclicality (revenues in this segment can rise and fall significantly from period to period). When sales are softer than expected (as they have been so far this year), Xyratex's customers will of course be reluctant to invest in growth, resulting in quarterly revenue for Xyratex that has fallen dramatically.

Sales also fell because of component shortages resulting from the earthquake in Japan. Xyratex itself does not have operations in Japan, so there are no direct costs in that respect, but customers who can't procure core components from Japan are reluctant to purchase components from Xyratex that they can't assemble without the complementary parts from Japan.

One major owner appears to believe that the problems are short-term; the company is 12% owned by Royce and Associates, a firm focused on value investments. The company's board of directors appears to concur, as Xyratex recently authorized a buyback of $50 million. At today's stock price, this would represent more than 15% of the company's shares outstanding. Despite the buyback, management expects to finish the year with $100 million in cash, meaning management expects the company to generate another $50 million of cash from the business between now and the end of the year.

In its quest to earn more, the company also benefits from a very favourable tax environment. For this Bermuda-incorporated company domiciled in the UK with manufacturing operations in Malaysia, taxes are nowhere near US business rates. As a result, operating income has been a decent proxy for net income, allowing the company to keep more of what it earns.

Not all of the issues are short-term, however, as there are some potential problems that could hurt the company in the long run. Customer concentration is high, and continues to increase. Companies in the storage space have been consolidating, giving them greater resources to research and develop the products they currently buy from Xyratex, and the market power to lower Xyratex's margins.

Furthermore, as a player in the fast-evolving technology space, Xyratex is only as good as its newest products. There is the risk that the company will fall behind the competition as the cloud-computing world continues to evolve. Investors must ensure that they understand the competitive threats facing the company from not only continuously evolving specs, but potential disruptive technologies that can alter the competitive landscape.

Disclosure: No position

The stock has fallen by 40% in just the last three months, as both the company's financial performance and its outlook have been below estimates. If the problems the business faces are short-term in nature, this is the kind of situation where value investors with a long-term view can generate strong returns.

In the early part of 2011, PC sales have been lower than expected, reducing demand for the company's products. One of Xyratex's two segments derives revenues in large part from the capex investments of storage firms, which results in heavy cyclicality (revenues in this segment can rise and fall significantly from period to period). When sales are softer than expected (as they have been so far this year), Xyratex's customers will of course be reluctant to invest in growth, resulting in quarterly revenue for Xyratex that has fallen dramatically.

Sales also fell because of component shortages resulting from the earthquake in Japan. Xyratex itself does not have operations in Japan, so there are no direct costs in that respect, but customers who can't procure core components from Japan are reluctant to purchase components from Xyratex that they can't assemble without the complementary parts from Japan.

One major owner appears to believe that the problems are short-term; the company is 12% owned by Royce and Associates, a firm focused on value investments. The company's board of directors appears to concur, as Xyratex recently authorized a buyback of $50 million. At today's stock price, this would represent more than 15% of the company's shares outstanding. Despite the buyback, management expects to finish the year with $100 million in cash, meaning management expects the company to generate another $50 million of cash from the business between now and the end of the year.

In its quest to earn more, the company also benefits from a very favourable tax environment. For this Bermuda-incorporated company domiciled in the UK with manufacturing operations in Malaysia, taxes are nowhere near US business rates. As a result, operating income has been a decent proxy for net income, allowing the company to keep more of what it earns.

Not all of the issues are short-term, however, as there are some potential problems that could hurt the company in the long run. Customer concentration is high, and continues to increase. Companies in the storage space have been consolidating, giving them greater resources to research and develop the products they currently buy from Xyratex, and the market power to lower Xyratex's margins.

Furthermore, as a player in the fast-evolving technology space, Xyratex is only as good as its newest products. There is the risk that the company will fall behind the competition as the cloud-computing world continues to evolve. Investors must ensure that they understand the competitive threats facing the company from not only continuously evolving specs, but potential disruptive technologies that can alter the competitive landscape.

Disclosure: No position

Wednesday, April 13, 2011

MCW Energy Group

The following is a sponsored post, paid for by MCW Energy Group. Content was provided by MCW Energy Group. The site's author does not own any MCW Energy Group Securities.

MCW Energy Group (“MCW”, “the Company”) is a Canadian holding company with two principal portfolio companies, a fuel distributor based in Southern California, and a break-through oil sand recovery venture with operations in Utah. MCW is a public company trading on the on the Frankfurt exchange under the symbol MW4.

MCW’s oil sand recovery technology, a leader in the industry with respect to environmental safety and efficiency, has the potential to open vast U.S. oil sand reserves to production. The Company expects rapid growth, both from sales of crude oil recovered from Utah oil sands under lease, and through improved competitive positioning in its core fuel distribution business. MCW’s two primary operations are:

• McWhirter Distributing Co., a leading distributor of branded and unbranded gasoline and diesel in the West Coast of the United States, and

• MCW Oil Sands Recovery LLC (“MCWOSR”) which will produce and sell oil extracted from oil sand reserves under lease in Utah.